During the heyday of harness racing in New York, when crowds of over 30,000 were commonplace at Roosevelt Raceway, one of the most popular and charismatic drivers on the circuit was Quebec native Lucien ‘Loosh’ Fontaine. One of the sport’s first true catch drivers, and the pilot of 1986 U.S. Horse of the Year Forrest Skipper, Loosh was also a pioneer off the track - a main force behind drivers getting paid straight from the purse pool. Lucien was finally voted into the U.S. Hall of Fame this past year, but sadly passed away before the induction ceremony, scheduled for the summer of 2023. By Debbie Little.

During the heyday of harness racing in New York, before the OTB was established and crowds of 30,000 people were still commonplace at both Roosevelt and Yonkers, one of the leading drivers of the era was Canadian, Lucien ‘Loosh’ Fontaine. The Quebec native was as well-known as any other athlete who walked the streets of Manhattan at the time, and he was as charismatic as he was famous. ‘Loosh’ was recently chosen to enter the U.S. Harness Racing Hall Of Fame, and although he was thrilled to hear the news, he sadly passed away before the induction ceremony could take place, scheduled for the summer of 2023. Rest in peace Mr. Fontaine; we’re proud to tell your story.

Lucien Fontaine passed away in September of 2022, and hadn’t sat behind a horse in 34 years, so many of today’s top horsepeople have no idea who he was - other than someone who was recently chosen to enter the hallowed United States Harness Racing Hall of Fame in Goshen, New York.

Perhaps today’s horsepeople need a history lesson though, because without realizing it, they all owe Lucien a debt of gratitude.

“He basically made it so that every driver and trainer is paid directly from the purses rather than trying to bill the owners,” said Freddie Hudson.

Hudson’s dad, Billy, was a top driver on the Yonkers-Roosevelt circuit in the 1950s and 60s, and at 9 or 10-years-old, Freddie first met ‘Loosh’ in the paddock at Yonkers.

According to Hudson, Fontaine was on the Board of Directors of the Standardbred Owners Association of New York (SOANY) and was the driving force responsible for getting the 5% driver’s commission taken out by the track. Fontaine was aware of the practice, which was already in place with Thoroughbred jockeys.

“It was like pulling teeth to collect your money,” said Hudson, “and I think it changed the sport. I don’t know if a lot of the guys racing today could ever handle not getting paid. Carmine [Abbatiello] could probably bring his old billing out and he would be owed about $1 million. Lucien could do the same.

“They’re paid [automatically now] and they owe this to Lucien Fontaine. Lucien’s the one who got it put through.”

Abbatiello remembers plenty of drives that he - not by choice - did for free.

“Back then, the trainers would get the 10% [by billing the owners] and they just wouldn’t give it [5%] to you,” said Abbatiello. “It was a big thing because a guy would owe you $10,000 and you’d never get paid.”

Fontaine was also a member of the New York State Racing Commission’s rules committee and fought hard for pre-race testing for both Standardbreds and Thoroughbreds in New York, as well as getting long-term insurance and pensions for horsemen.

It’s not just for his actions off the track however, that Fontaine deserves to be feted. He was a top driver during the heyday of racing in the 60s and 70s, even though unlike many, he was not raised in the business.

Fontaine grew up with 11 siblings in Pointe-Aux-Trembles, Quebec, the child of a shoe factory worker, but he was not interested in following in his father’s footsteps.

Lucien loved horses and started out working for the local milkman. The job, he said, was extremely easy because the horse did all the work. Then there was harness racing.

Fontaine grew up near Richelieu Park, which had cars and then Standardbreds.

“In the beginning, he was either going to race cars or horses,” said Marc Fontaine, Lucien’s son. “He liked anything that moved, went fast and had a motor in it.”

At age 14, ‘Loosh’ spent the summer working with the horses while also working for about half the year in the factory with his father.

When he informed his dad that he wanted to go with the horses full-time, his dad’s response literally knocked Fontaine into some shoe racks. His father refused to let his son become what he thought would be a bum.

Eventually, before Fontaine’s father would let him go, future Hall of Famer Keith Waples had to sign a letter basically stating that while Fontaine was in his employ he would be responsible for him and was more or less his guardian.

In 1957, Fontaine moved on to work for another future Hall of Famer, Clint Hodgins, and made his way to the U.S.

Anyone that ever knew Lucien was well aware of his particular talent for telling a story.

He spoke little English when he left Canada, and he enjoyed telling the story of his first experience in a New York diner.

Not knowing how to say what he wanted in English, Fontaine pointed at what another customer was eating. The server responded, ‘Oh, you want steak and eggs.’

Fontaine said that experience helped him learn English much quicker because he was getting tired of eating steak and eggs every day, since that was all he knew how to order.

He also loved to share the story of his first time driving from Monticello Raceway to Roosevelt Raceway.

He once said at a Roosevelt Raceway reunion that it once took him longer to drive from Monticello to Roosevelt than to drive from Monticello to Montreal.

For some perspective, the drive between Montreal and Monticello is about five-and-a-half hours while the drive between Monticello and Roosevelt is supposed to be about two.

What took Fontaine so long that first time?

Apparently, he could see the lights of Roosevelt off in the distance but just couldn’t figure out how to get there. He just kept driving up and down the highway for hours until he spotted a police officer on the side of the road.

He explained that he needed to get to Roosevelt and the cop pointed and said: ‘It’s right there’.

Fontaine responded: ‘I know, but I don’t know how to get there.’ The cop took pity on him and led him to the track.

It was reported that Fontaine did not move his car for quite some time after that experience.

Lucien believed that his time in the Hodgins stable helped get him noticed when, in 1959, at the age of 20, he put a new lifetime mark on 21 of Hodgins’ 24 horses.

By 1961, Fontaine was the top driver at his home track, Richelieu Park. His father passed away two days before the start of the meet, but Lucien said it was OK because his dad was already proud of what he had accomplished.

During his time in Monticello, Fontaine met the love of his life, Marsha. Hall of Famer Bill Popfinger was with Fontaine the day he met her.

“We went to the grocery and were walking casually down the street and she came walking by,” said Popfinger. “We started talking a little and the next thing he did was he got her number and took her out on a date… the rest was history.”

After several years as a top dog at Monticello, Fontaine eventually made the move to take on the best in the game on the Yonkers-Roosevelt circuit.

Just like everywhere else he went, he became one of the top drivers there as well.

As Fontaine was finding success in New York’s harness racing big leagues, his boyhood friend Rod Gilbert was doing the same in New York, in the National Hockey League.

Lucien grew up with both Gilbert and Jean Ratelle, two of the three members of the New York Rangers’ GAG (Goal-A-Game) line.

Gilbert was known as ‘Mr. Ranger’ and was the first player in Rangers history to have his number retired.

Fontaine and Gilbert were kings of New York in their respective sports and when they walked down Broadway in New York City, just as many autograph seekers came up to Fontaine as they did Gilbert.

Emmy award-winning sportscaster Sal Marchiano, who worked in radio and television in New York for 44 years, was friends with Gilbert, who introduced him to Lucien.

“They weren’t just big sports heroes, they were friends to me and my wife,” said Marchiano. “You have friends, but then you have really close friends, and that’s what Lucien was to me.

“When we went to his house in Tarrytown, the trophies and all that were just in one room. You would not know in the rest of the house what he did for a living.”

Fontaine wasn’t just a great driver; he was also a smart businessman.

“He realized a long time ago that you really couldn’t make a living off the 5 or 10%, you needed to own the horses that you drove,” said Hudson. “And he bought horses, so he was making almost 100% where other people were making 5 or 10%.”

Something that is considered typical today is catch driving, but back then it wasn’t. Fontaine, who was - according to Hoof Beats magazine in 1969 - ‘America’s leading 100% non-training catch-driver’, was one of the pioneers that helped make catch driving a typical thing.

Barry Lefkowitz, President of the U.S. Harness Writers Association, became publicity director at Roosevelt in 1985, and although this was near the end of Fontaine’s career, Lefkowitz knew how talented he was.

“I have very fond memories of him when I was getting hooked on harness in the 60s and 70s,” said Lefkowitz. “He was always one of the leading drivers on the New York circuit at the time.

“One of the interesting things about Fontaine was in 1973, he won the Messenger Stakes on a catch drive with Valiant Bret. Back in those days most guys trained and drove their own, so to win a Triple Crown race on a catch drive in the early 70s, I think is a testimony to his ability that people wanted to use him in a big spot.”

Fontaine owned and drove many top horses, but it wasn’t until 1985-86 when he had two magical seasons with that once-in-a-lifetime horse, Forrest Skipper.

Forrest Bartlett owned Forrest Skipper, and after a two-year-old year where he went 8-6-2-0, he realized the horse was good enough to be racing in New York at three. Bartlett asked his friend Norwood ‘Woody’ Truitt for advice.

“I said to Norwood, ‘this horse needs to go up the road to race next year,’” said Bartlett. “‘You got anybody up there you recommend?’ He said ‘Forrest, ain’t but one honest guy up there and that’s Lucien Fontaine.’ He put me in touch with Lucien and we stayed in touch from then on.

Forrest Skipper had the misfortune of sharing a birth year with the great Nihilator, and although he never did defeat that one at age three, he did give him a few good tussles. The following year, in 1986, Forrest Skipper blossomed into a superstar.

“I think it’s the best year I’ve ever had in my whole life. I was in my late 30s and I went to every race he went to his last year. It was just a fantastic year and a good time, and I’ve tried to get another one ever since.”

One race that sticks out in everyone’s mind from that year is the U.S. Pacing Championship at The Meadowlands. Even though there were approximately 60 horses eligible to enter the event, Loosh had just qualified his star in 1:51.3 - the fastest qualifier ever at that time - and incredibly only TWO names were dropped into the box: Falcon Seelster and Forrest Skipper. It ended up being a match race.

Coming into the race, Falcon Seelster, considered to be a half-mile specialist, had set world records on both a 1/2 -mile and 5/8ths-mile tracks, and had won his last seven in a row. Forrest Skipper was a perfect nine-for-nine on the season.

Typically, in a two-horse race, one goes to the lead and the other sits behind him, but Fontaine was never the typical driver.

Before the race Delvin Miller asked Lucien if it was going to be the typical boring match race with fast first and last quarters only. Loosh told Miller to stick around, and promised it would be a race from start to finish. He said that he didn’t care if he got parked to the half in :53, that he was driving on until he got there, and if Harmer parked him, that Falcon Seelster would pay the price for it in the end.

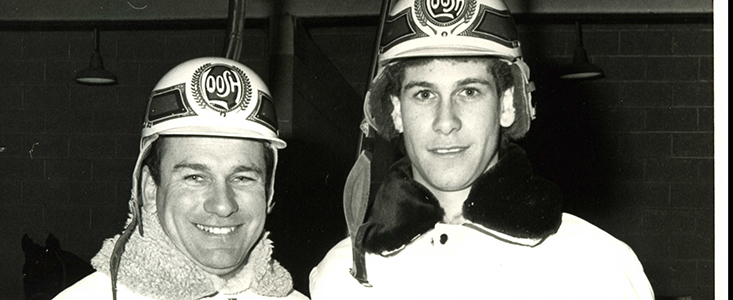

LUCIEN & MARC FONTAINE

Legend has it that after the two horses went their final warm-up miles, Lucien asked Harmer, in front of a few others in the paddock, how his colt was that night. When Harmer said “really good,” Fontaine countered with something along the lines of “That’s good, you should be able to be second in there tonight.” To which the crowd around them laughed heartily.

Lucien was known to be a showman, but it was always in good fun, and he was never disrespectful to his peers.

When the wings folded and the match race began, as expected, Tom Harmer left with Falcon Seelster, but Fontaine, true to his word, didn’t drop in. Instead, he sat parked right off Falcon Seelster’s flank through an opening quarter of :27.2.

Fontaine kept Forrest Skipper right at Falcon Seelster’s neck through a half in :54.2. He’d give him his head a little, and as soon as Harmer would tap Falcon Seelster with the whip to drive on, Lucien would immediately take hold of his charge to conserve him. Going to the three-quarters, Fontaine let his champion pace, and when Forrest Skipper got the green light, it was time for the familiar ‘Loosh with a whoosh’, as the pair opened up a quick seven lengths, before hitting the three-quarter pole in 1:21.4.

It was a race against the clock from there, but an incredibly strong head wind through the stretch was credited for slowing the final quarter, as Fontaine and Forrest Skipper hit the wire in 1:53.3.

“There was something about Loosh, he never would brag a whole lot before a race but after it was over, he could tell you something,” said Bartlett.

What made the experience with Forrest Skipper so much more special for Fontaine was that his son Marc trained the horse, so they went on that great ride together, all the way through an undefeated season (15-for-15) and 1986 U.S. Horse of the Year honours.

In 1989 however, at the age of 49, Lucien Fontaine walked away from driving after a heart attack and a resulting triple-bypass surgery.

Since all of Fontaine’s siblings and his parents were gone by the age of 50, he decided to enjoy what time he might have left, and spent the next 17 years traveling around the world with Marsha, until she passed away from cancer in 2006.

“We really felt blessed to have him for the last 16 years, ever since my mom died,” said Marc. “We really felt he was going to die of a broken heart, and his health wasn’t great. He was a fighter though, and he outlived anybody’s expectations.”

Trainer Bobby Hiel was 10-years-old the first time he met Fontaine in Monticello, but the pair reconnected in 2006, after Hiel moved to Florida.

They were the closest of friends ever since being reunited and spent a lot of time together.

“I said to him it was like what Frank Sinatra said about Dean Martin. He’s my brother by choice,” said Hiel. “That’s how we felt about each other. There’s nothing we wouldn’t do for each other.”

Hiel said one afternoon, not too long ago, he and Fontaine were sitting outside a restaurant near the beach in Pompano and they struck up a conversation with some guys sitting nearby.

Hiel introduced himself and Fontaine, and one of the guys said: ‘You’re Lucien Fontaine? You put my son through college. He used to bet on your horses.’

Fontaine was also the best of friends with both Gilbert and Marchiano, and when Gilbert passed in 2021 and Fontaine was unable to attend the service in New York, Marchiano found a way to include him.

“When Rod passed away it was like my brother had passed away,” said Marchiano. “It’s the same with Lucien. Judy Gilbert asked me to give the eulogy at the funeral mass, which I did for Rod.

“While I was writing it, I called Lucien to get some more detail about them growing up in Quebec, which he gave me. No one else had that stuff about how they grew up. It’s difficult to use the word ‘compliment’ when it comes to eulogies, but Jean Ratelle sought me out afterwards and was highly complimentary that I had gotten it right about their lives in Pointe-Aux-Trembles.”

Although Fontaine had been nominated many times over the years, perhaps the phrase out-of-sight, out-of-mind, played a part in why it took so long for him to have his hall of fame moment, and indeed it was USHWA’s Veterans committee that selected him for the honour this past summer.

“When I called him from Goshen to tell him that he made it, on that July afternoon, he was so overjoyed when I spoke to him,” said Lefkowitz. “He was so elated and couldn’t wait to get involved with the hoopla that was going to follow in the next year.”

Sadly, Loosh will now only be at the festivities in spirit.

Forrest Bartlett and Fontaine also stayed in touch through the years, after the Forrest Skipper days, and Bartlett remembers getting a call from him this past July.

“When Lucien found out that he was going into the Hall of Fame he called me up and said ‘Forrest, I want to thank you for getting me into the Hall of Fame.’ He said ‘Forrest Skipper is the reason I got in there.’ Lucien did not have to do that. There’s not anyone around anymore in the horse business like Loosh.”

It is comforting to his friends and family that at least Fontaine lived long enough to know he’d been selected, but many are sad that it didn’t happen earlier when he could have enjoyed it.

“They should have put him in a while ago, but they waited,” said Abbatiello, who was inducted into the Hall in 1986. “What did they wait for?”

Hiel was very close to Fontaine and Abbatiello, and was the one who called Carmine to let him know of Lucien’s passing.

“Carmine said ‘He should have been right next to me,’” said Hiel. “It’s like Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth.”

Ed Lohmeyer raced against Fontaine back in the day and thought he was always a total gentleman.

“That crowd back then was a tremendously talented group,” said Lohmeyer. “Insko, Gilmour, Abbatiello and Herve, there were so many of them and Lucien was one of them. They [people today] don’t even remember him. I don’t think any of the guys today know how talented he was. He was a very, very cagey guy. He knew a lot of the horses he was in against and knew a lot of the drivers he was in against, so that was to his advantage when he hit the racetrack. I think he had a great head on his shoulders.”

John Manzi, Lohmeyer’s cousin, also drove with Fontaine back in the day.

“Everybody wanted to know Lucien, he was one of the best,” said Manzi. “I remember when he won all four ends of the twin double. For a guy to win four races on a card then was very unusual.”

The twin double was a wager at Monticello where you had to correctly pick a double then turn in your ticket to be eligible to select the winners of the next double, usually a race or two after the first one.

“He was a talent right from the get-go,” said Manzi. “When you raced against Loosh, you were racing for second money. And I raced with Lucien and Carmine both.

“He should have been in the Hall long ago. His numbers, back in the old days, that was a lot of races to win.”

Mike Lachance is 12 years younger than Fontaine, but remembers hearing about him growing up.

“In the last 20 years if somebody wasn’t in the limelight, they just forgot,” said Lachance. “Lucien was around during the great days of harness racing. The great days of Roosevelt and Yonkers with all the old timers, with Haughton and Dancer and Insko and Carmine. And for him to get into the Hall of Fame with the recognition with all of them, it meant so much to him.

“He’s gone but he’s going to be remembered. Sometimes I talk about those days with the younger guys today and they look at me a little funny because they weren’t there, and they don’t remember how great that generation was.”

This feature originally appeared in the December issue of TROT Magazine. Subscribe to TROT today by clicking the banner below.